Just when the game was poised for a growth spurt in the Roaring Twenties, instead it retrenched. Its profile was diminished, albeit briefly, while under foot, the roots continued spreading. After reemerging, Washington soccer proved unshakable. It would survive a shifting economy, The Great Depression and another World War, emerging with a new generation, ready to move forward and establish the Northwest corner of the nation as a footballing bastion.

Puget Sound’s Northwestern League survived World War I only to die quietly shortly after. When Carbonado wrapped-up the double by taking the McMillan Cup in March 1920, the league had six clubs, five associated with mining or shipping firms. So, it was surprising when no competition could be organized for the following winter or the next. It marked the first such lull since 1904, before the Northwestern League was first formed.

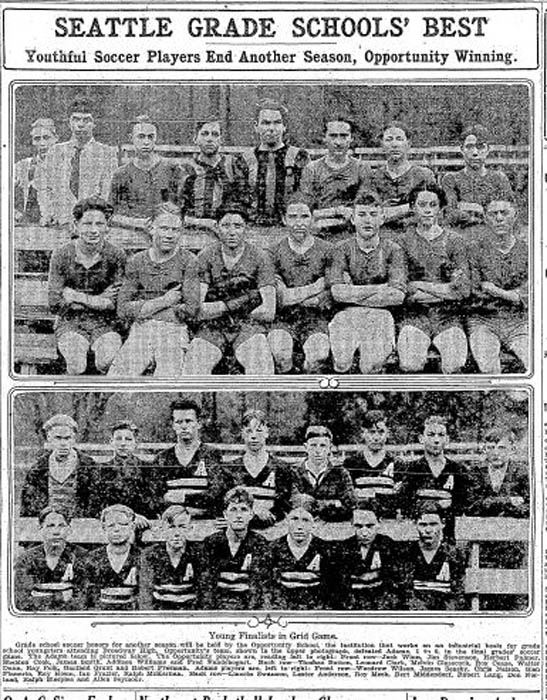

There would continue to be challenge matches during this down time, and interest in the game had not waned. In fact, with doubts as to safety of gridiron football, soccer was the preferred autumn sport in schools. Fifty-four grammar schools throughout Seattle organized teams in 1921. Many of these boys would matriculate and eventually find their way to senior teams in the years to come.

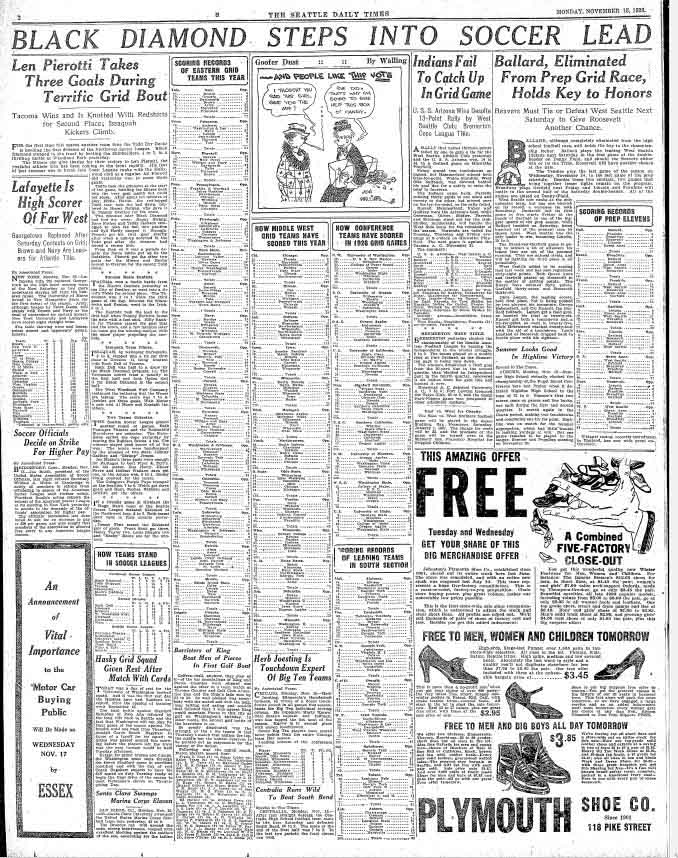

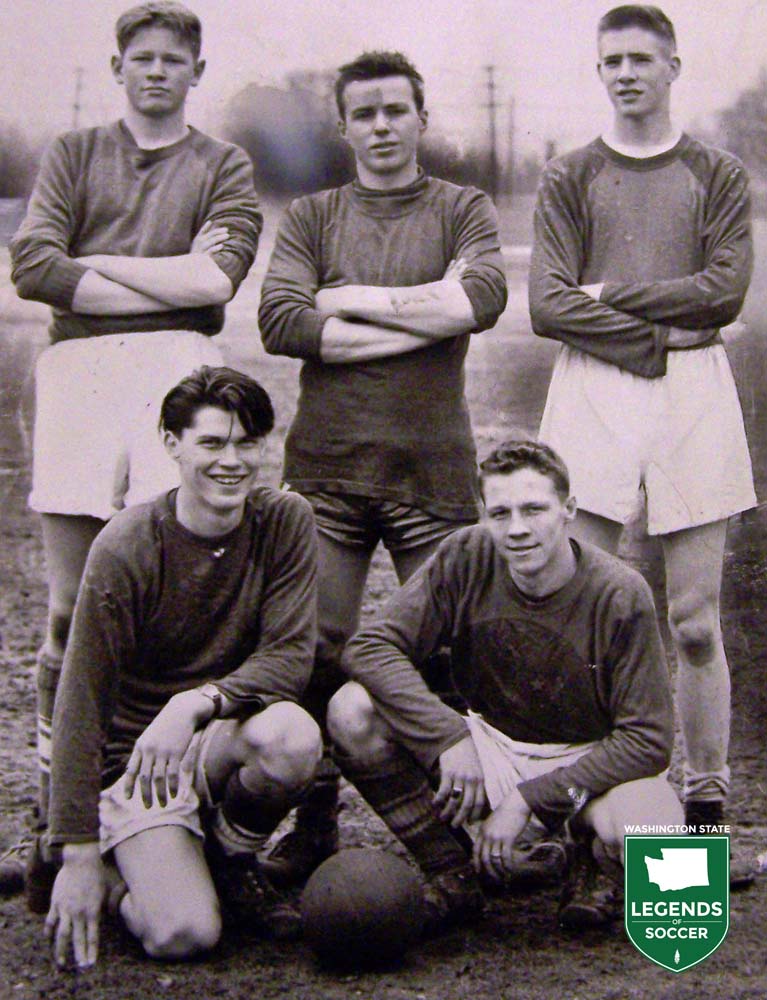

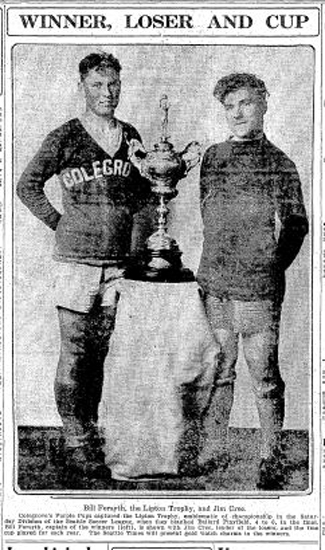

Finally, in November 1922, the Seattle City League was established by four disparate senior clubs: Boeing Airplane Company, Maple Leaf American Legion Post, West Seattle Athletic Club and Woodland Park. There was also a four-team junior division for graduates of the grammar school league. In 1926, the youth of Seattle and, later, Puget Sound were bestowed a magnificent prize to play for Scottish tea magnate Sir Thomas Lipton answered a request from a local official, sending a 3-foot sterling silver trophy valued at $1,500.

Just three years earlier, William Boeing had made a name for himself by making the first international airmail delivery, from Vancouver to Seattle’s Lake Union, via seaplane. Maple Leaf’s legion post served as a second home to many returning veterans. Woodland Park was a holdover from the Northwestern League, whereas West Seattle was emerging as an increasingly accessible peninsula. Black Diamond and Carbonado remained mired in the nationwide coal strike. Employees playing for the company-sponsored side would not receive any pay, however in the mines they would be assigned to preferred duties on the day shift, allowing them to train in afternoons.

Evidence of a pent-up demand for soccer was clear. More than 2,000 spectators found their way to Hiawatha Park for the West Seattle-Maple Leaf match that concluded the league’s first half. The senior division immediately grew in size and scope, adding teams from Tacoma and Valley City (Renton) in 1923. The mining towns soon joined, along with a second Tacoma side, Todd Shipyard. Within two years the first division had doubled in members, and in 1926 over 8,000 cheering spectators wedged into Upper Woodland to see Todd Dry Dock defeat Electro Dentists.

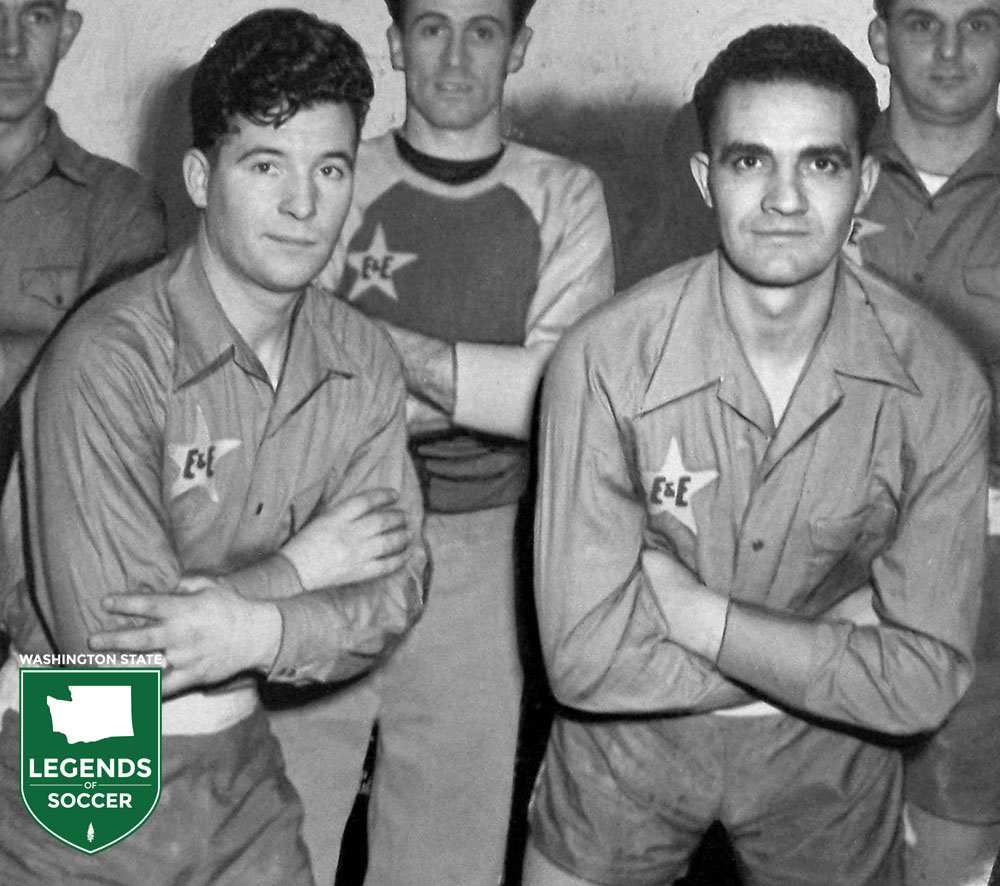

Of the junior teams, the Vikings of Seattle’s Ballard neighborhood, joined the senior division after three seasons as juniors. The Vikings also organized a women’s program, and the Scandinavians became one of the most stable league members of the era. The Vikings, Carbonado, Black Diamond and Maple Leaf (known as the Electro Dentists beginning in 1926) all managed to weather the first years of The Great Depression. The game was popular in other areas. Bellingham Normal (now Western Washington University) organized women's teams beginning in 1926 as a Whatcom County men's league sought affiliation with the Washington State Football Association.

One notable club did not survive, however, although it’s debatable whether it was related to the worldwide economic woes or geographic isolation. In Washington’s southwestern corner emerged a new power, the Longview Timber Barons. The club was conceived as wintertime entertainment for the logging and mill town of Longview, located across the Columbia River from Oregon’s northwestern spur. No sooner did the Timber Barons join the Portland league headquartered 50 miles south than their domination commenced.

The Timber Barons won five consecutive league championships (1926-30). Most of their players were Canadian or British by birth, with a few, such as Tuffy Davis, plucked from the Seattle league. Representing Oregon, Longview won the 1926 Northwest championship and also claimed the 1929 Washington knockout title. Eventually they wore-out their welcome in Oregon. In 1931, the state leaders arbitrarily decried that the Timber Barons play their Bennett Cup (Oregon knockout cup) matches on the road in Portland. In response, Longview withdrew.

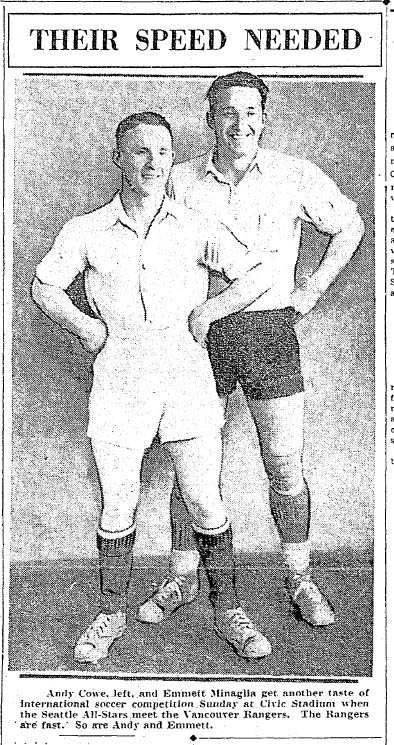

During the Twenties, Washington and Oregon initiated semi-regular clashes to determine supremacy of Cascadia. On occasion, it was picked teams of league all-stars but more often it was the clubs who won their respective state knockout tournament. Washington also met Vancouver area aggregations throughout the Thirties. Although bragging rights were at stake, the host would provide lodging and meals, including a postgame social. Gate receipts were directed toward charitable causes or youth soccer development.

In order to recover expenses or raise funds, senior league matches would be moved from public parks to grounds with gates and seating. Seattle’s Liberty Park, Dugdale Field, White Center and Civic Field were primarily baseball venues. They were available during winter but, to preserve grass, were off-limits in early spring as the diamond season approached. Civic Field, located on the site of Memorial Stadium, offered 15,000 capacity yet a bumpy, dirt pitch. When Lower Woodland Park fields opened in late Thirties, those fields became virtually dedicated to soccer play alone.

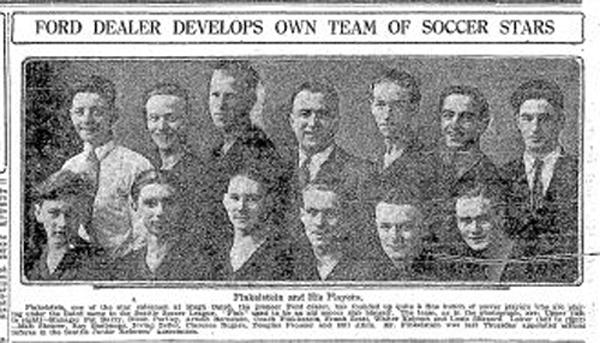

Throughout the Depression, team sponsors tended to be small businesses. Club personnel might remain intact for the most part, but its sponsor might rotate every few years. For example, Piston Service/Westerman Clothiers/Mrs. Wickman’s Pies was an 8-time league champion from 1931-48. Once Prohibition was repealed, breweries offered support. Prior to World War II, there were two ethnic sponsors, the Vikings and German Society. Once war was d, the latter immediately found a commercial sponsor.

Senior league membership remained steady through the war, but only because of some unique circumstances. In 1944, Italian prisoners of war who volunteered to help Allies were placed on U.S. military bases and given work, accommodations and privileges. Among the freedoms afforded those Italian Service Units in Puget Sound was playing in the state soccer league. At first, they were recruited as individual ringers (Italy was recognized as the sport’s world power, having won the 1934 and 1938 World Cups). During the 1944-45 season, however, they comprised three of the first division’s seven teams., and Seattle’s Fort Lawton-based ISU won the league.

Washington’s postwar economy and culture was vastly different from 10 years before. Hydroelectric dams on the east side of the state had given rise to aluminum manufacturing and aircraft production on the west side. Planes and jets for both military and commercial purposes would create a behemoth of Boeing, attracting workers from western Europe. They would be bringing their trades as well as their footballing know-how and sharing it with upcoming youth who had grown to love the game.

As the Forties came to a close, for the first time in Washington would come an exhibition of skill the scale and depth of which had never before been witnessed by the masses. England’s Newcastle United was drawing huge postwar crowds to historic St. James’ Park to witness the likes of goal-scoring phenom Jackie Milburn. Soccer leaders in Seattle scratched out sufficient funds to lure Newcastle for a postseason tour stop in June 1949, the Magpies coming off a fourth-place finish in the league.

Newcastle would shred the local collection of all-stars, 11-1, but manager George Martin offered some sage parting advice: “Dress up your game. Get someone to build you a turfed pitch and watch the improvement in play of your teams, and the appeal it has to the city.”

Within months of the match, the Washington State Football Association would take action. Bleachers and new goals were erected at Lower Woodland. Meanwhile, senior teams would be allowed more roster spaces and match substitutes, allowing for junior players to be added and given invaluable experience. Without question, the game was prepared for greater things in the Fifties and beyond.